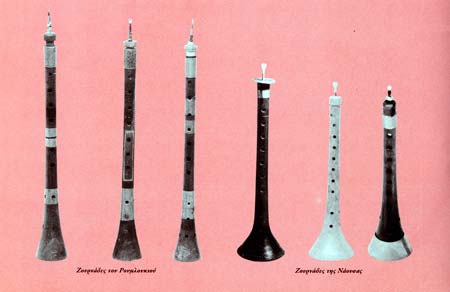

The Greek clarinet “zournas”

The Greek clarinet, the zournas, belongs to the family of oboe instruments with a double reed. It is regarded as the same to the ancient flute which existed since the time of Homer according to historical, philological and conjectural evidence. According to the composer Pavlos Karrer, the zournas was considered as the national flute of the Greeks until the regular clarinet took its place. In his memoirs he mentions that: “I saw them singing and dancing while playing their national flute and the tambours (daouli)”. In the whole country but especially in Macedonia there are many wall-paintings and hagiographies of the Byzantine or post-Byzantine era where the zournas and the daouli are represented. No one of the philhellenes or the foreign travelers like Pouqueville, R. Chandler or Lord Byron liked the zournas. In Foivos Anogeiannakis’ research about the traditional Greek instruments it is mentioned that: “If we take into consideration their different musical education it is very hard for those foreigners to feel the melody of the Greek folk music. Pouqueville thinks that the zournas is a terrible musical instrument”.

But when you have nothing to do with the Greek culture in general how could you not find these instruments terrible?

In Imathia and generally in Macedonia the zournas is of two types. The first one is shorter (35 cm.) and is played only in Naoussa. The second one is long (65 cm.) and is common in central and eastern Macedonia (Herakleia Serres). The longer the zournas, the deeper the sound produced.

This musical instrument has three basic parts:

-

The main part, the “body” of the instrument that has the shape of a funnel and is called “tatara”

-

The second part is called “kleftis” or “pistomio” or “kefalari”

-

The last part is called “pipnar” or “piska” with the “tsampouna”

The main part is made of different kinds of wood in view of the opinion of its player (zournatzis) who is also the one that manufactures the instrument. The most common types of wood are maple-wood, apricot-wood, olive-wood, walnut-wood, cherry-wood, arbutus-wood and beech-wood. The wood has to be dry, without knots and stable so that the sound produced will be deep and loud. Furthermore, they used to boil the wood in water mixed with salt or ashes in order to avoid its cracking. Nowadays, the zournas is not anymore hand-made. Before the year 1970 its manufacturing was a difficult and long-lasting procedure as it had to be made by using knives, razors and glasses for its polishing. The drilling of the wood with a glowing metal was very difficult and took many hours. After the main part was made they had to make the holes, seven at the front side and one at the back between the first and the second hole. The distance between the holes is 3, 5 cm. There are also some holes on the “tatara”, the funnel shaped part, three at its front side, one at the back (between the first and the second one) and four more, two on each side of the first three holes.

The organ-player uses only the 7+1 holes that are on the main part. The rest of the holes remain always uncovered but are instrumental in the good quality of the sound. If we cover these holes the sound becomes weaker and the tonality as well as the intervals change.

The holes of the zournas are not everywhere the same.

When the main part of the instrument is made it is time to attach to its upper part the “piska” with the “tsampouna”. It is about a thin cylinder usually made of sheet-brass where the double reed is firmed.

The reed is considered to be the “elongation” of the organ-player’s tongue, the mean to show his sensitivity.

This part of the instrument is usually made of wild reeds. Their diameter should be about 5-10 cm. and they can be found at the banks of the rivers Aliakmonas, Loudias and Axios during the months September and October. They are cut in pieces of 20 cm. and after being cleaned up they are left for some days in the sun in order to get dry. If the organ-player likes his reed soft he will only leave it under the sun for about one week. But if he likes it harder he will leave it for two or even for three weeks.

The reed of the instrument has a diameter about 1,5-3 cm. The short type of the zournas has a smaller reed than the long one. But the length of the reed has also to do with the instrumentalist; how strong he can blow and how deep it goes into his mouth. Each of the pieces of the cut reeds mentioned before is cleaned up on its inner sides with retrogressive movements. They are placed into water mixed with vinegar and tied to a wooden cylinder that has exactly the same shape with the “piska”, where the reed is finally going to be attached to. After that, the organ-player presses it with his fingers. The result of this pressure is a double reed. In order for the reed to keep this shape, the instrumentalist presses it harder with a glowing knife. After that he rounds it in order to protect his lips and he also burns its edge in order not to be sticky. This last part will be repeated many times. It is very common for the organ-players to burn the edge of the instrument with their cigarette every time it becomes sticky and makes their playing hard.

When the organ-player blows, the parts of the double reed vibrate and produce a very penetrating and impressive sound.

Another part of the zournas is also the “pina” or “pena”, a disk with a diameter of 3-4 cm. made of horn or metal. Usually, it was a big coin with a hole in its center that was put on the “kleftis” through the reed. The “pina” is of great importance because the organ-player can place his lips on it and avoid any injuries. Furthermore, it also decorates the instrument. The players used to hang on it a silver chain with some “piskas” tied on it so that they would be able to use them immediately if the one they were using broke, crack or became sticky. The only disadvantage of these “piskas” was that they turned dry. Nowadays, they are being placed in a metal box with a tree-leave or a little piece of potato in order to keep the moisture of the air.

But the most important fact that is related to the sound produced is the organ-player himself. The way he blows and the way he plays this extraordinary instrument.

It is about a unique technique that is based on the simultaneous in- and exhalation. In other words, the organ player takes breaths from his nose without stopping playing the zournas. This air is being held in his mouth and when it is used he takes another deep breath. It is impressive that he does not stop blowing while doing the above procedure.

Furthermore, it is important that the reed is kept soft, that’s why it is poured with water or wine.

According to Foivos Anogeianakis’ research: “the range of the zournas’ diatonic scale is of one octave and two musical sounds. But if the instrumentalist blows stronger and presses his lips harder there could be produced many more musical sounds, which are not used very often as they exhaust the organ-player. The tonality depends on the length of the zournas as well as on the size of the reed. A man who can play the zournas well is able to produce a melody that relates to the Greek tradition by using some of his “tricks”, like the instant covering of all the holes”.

This musical instrument is “underprivileged” in Imathia as well as in Macedonia generally. People never say “let the clarinet (zournas) play”. They always say “let the tambour (daouli) play” even though there are two types of zournas and only one type of daouli.

The Greek tambour “daouli”

The daouli is known since the Byzantine era and was particular popular in religious ceremonies, a fact that is proved by the many wall-paintings that were found in many monasteries. There is also evidence that it was one of the instruments used during war in order to encourage the soldiers and to terrorize the enemy, especially when it was played together with the zournas. Makrygiannis makes references to this musical instrument, to the impact it had on the enemy but also to the encouragement it offered to those who used it.

Elder musicians of Roumlouki talk about the existence of many of those tambours. The organ-players of this instrument used to be part of the Sultan’s army in the past.

The daouli has not a definite size. Its size depended on the local customs and the height of the man who played it. If he was tall with long arms he would carry a daouli that could have a diameter of 80 cm. Unfortunately, nowadays this instrument has become smaller and its diameter reaches up to 56-60 cm.

The manufacturing of a daouli demands mastery and patience, especially as far as the process of the leather is concerned. The most appropriate kind of leather is of donkey, of wolf or of cow. The painful and dirty process of the leather is made in two different ways. The first one is to skin the animal very carefully in order not to cut the hide which is being dredged with salt and left in the sun to get dry. After it is dry enough it is put for 5 days in slaked lime in order to get rid of the fur. The animal’s hide is being cleaned from the fat with a spatula or a piece of glass. Afterwards, it is being oiled in order to be soft and smooth and it is stretched over two hoops. Holes are poked perimetric on its surface at intervals of 10 cm. and a rope that chocks the hoops up on the main frame is passed through these holes. The way the rope is passed through the holes and is tied up can be different from place to place. The cylindrical part of the daouli is made of wood. In the past years it was very difficult to manufacture this cylinder because of its measurements that could reach up to 60 cm. × 2m. The pieces of the wood were connected one to another with special tools in order to avoid the gaps between them. However, there were some holes on the cylinder (usually two, three or four but sometimes only one) that would allow the air that was concentrated in the inside of the musical instrument during its playing to find its way out. The organists of the daouli claim that every beating of the drum is that strong that it could kill a calf if it is hit on the right spot of its head.

Playing this kind of tambour has its own technique and the way of beating is instrumental in the sound produced. There are used two kinds of drumsticks. The one is long, about 40 cm. and thick. The second one is about 50 cm. and thinner; it looks like a cane and it can also bend. Most of the times, the daouli is manufactured by the man who uses it, just like the zournas. One of the two leather surfaces was a little bigger and thicker so that it would last the beating of the thick drumstick. The sound produced at this side of the tambour is strong and deep. The leather on the other side is thinner and the sound produced by the beating of the thin drumstick on it is more penetrating. Furthermore, the tuning up is of great importance too and it demands skills and mastery as it has to be combined with the zournas.

However, according to Foivos Anogeiannakis, there is no definite tonal relationship between the two sides of these tambours despite the obvious differences in the pitches produced. Sometimes, there is a tonal relationship between the daouli and the zournas, especially in orchestras whose members play a long time together. In the course of time the organ-player of the daouli gets used to the tune of the zournas. The daouli becomes the instrument that gives the tempo to the zournas, something very familiar to Greek musicians but very hard for foreigners to understand.

Anogeiannakis claims that there are two ways of playing the daouli that depend on the beat of the other instruments of the orchestra. A man who plays the daouli well often switches the drumsticks in order to beat the thick side with the thin stick and the thinner side with the thick stick. He also beats on the ground or on the wooden hoops. These are some of the “tricks” that help the organist to produce a wide range of different sounds. Even the spot of the leather surface beaten (whether it is the center or the edge) can change the tune of the sound. If the melody that is played by the other instruments is slow, the organist of the daouli beats the leather surface at long intervals with his thick drumstick and uses the thin one to do a tremolo.